My great grandfather, Larry Lewis, carried a leather bound autograph book on his travels. I have this battered and well-loved book containing over 100 autographs of performers of the period – from Marie Lloyd and Harry Lauder to the lesser known bottom of the bill artiste.

It was common for music hall performers to carry autograph books, passing them around dressing rooms and boarding houses during their week’s residency. Some of the entries are beautifully illustrated and would have taken some time — a means to while away the hours before the evening performances. Often a photograph was included, bringing those signatures to life.

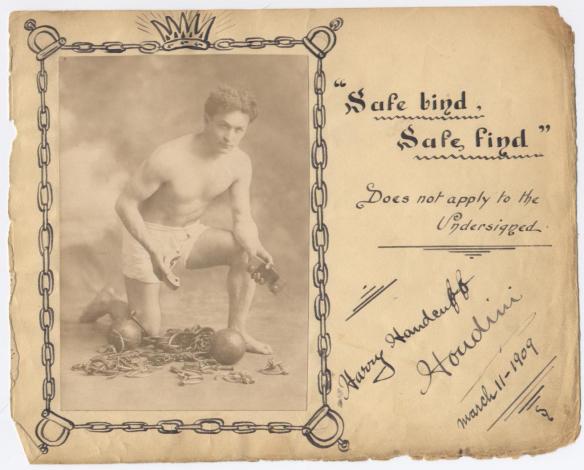

As a child, I gingerly turned the aged pages and at one particular entry, I was always awestruck — it was the autograph of Harry Houdini.

The autograph, with a muscle man style photograph, is dated 11 March 1909 and signed Harry Handcuff Houdini. There is a very careful pen and ink handcuff and chain illustration. During the week of 8 March, Violet, Larry and Houdini were performing at The Empire in Old Market Street, Bristol. Harry Day (sometime British agent to Houdini) was also Larry and Violet’s agent and this may explain the booking.

The programme at the Bristol Empire that week was described as ‘an attractive one’ and along with the top-billing star Houdini, Larry and Violet were also on the bill with the Dacey & Lewis Duo, a somersault and song combo; The Milliards, a parallel bar act; The Showells, duettists; Leo Merode, looping-the-loop on a bicycle; and Lottie Leighton, a dancer. Violet was reviewed favourably,

‘more pleasing than ever and her song, “She Sailed Away,” will be responded to with no little fervour before it is a night older, judging by the way the refrain was “caught up” by the gallery’.

The audience certainly was in good spirits! Houdini’s presence may well have had something to do with that.

Houdini, ‘The World’s Greatest Mysteriarch,’ was back in Europe to promote his new act, the Milk Can Escape. He was keen to move away from the handcuff act with which he had made his name, as he could not keep up with the ever-growing number of imitators and rivals. He needed something new to maintain his sensational reputation. Houdini had last been in Bristol in 1904. Advertisements had been running in the local press in the run up to this engagement encouraging punters to book seats ‘to avoid disappointment’. The capacity of the Empire was around 2,500; it was described as having ‘big house[s]’ every night as audiences flocked to see him.

Houdini’s dramatic and visually arresting posters for the Milk Can Escape proclaiming “Failure Means a Drowning Death” would have been showcased outside the Empire. Houdini’s tour of the United Kingdom had been accompanied by an endless series of publicity-seeking bridge jumps, jail breaks and escape challenges. These challenges were actively invited from members of the public. During his week in Bristol Houdini accepted two such challenges. The first on Wednesday evening (and reported in the Western Daily Press on Thursday 11 March) was presented by three local harness makers. Their challenge was that Houdini should free himself from a restraint, more frequently found in padded cells, in full view of the audience. The restraint itself was described as a sailcloth bag with collar and closed sleeves, fitted with straps and buckles. The escape challenge was met and Houdini freed himself in just over ten minutes, to the loud cheers of the audience. As per the motto Houdini set out in Larry’s autograph book – “Safe Bind, Safe Find Does Not Apply to the Undersigned”.

The second challenge was publicised in the Friday edition of the Western Daily Press (to take place at the second house that night) as follows:

Proposed by three asylum attendants (William Malcolm, Frederick Pohlman and Walter Green), their challenge was to strap Houdini to a ‘crazy crib’ (an asylum hospital bed) with a leather neck collar and straps to secure every part of his body. After they had strapped him down, they stipulated that none of the Empire staff or Houdini’s assistants were to interfere with the apparatus in any way. And as with the first challenge, the escape was to take place in full view of the audience.

“Will He Get Out?” screamed the challenge advert. Would Houdini be “Defied”? Houdini wriggled, gyrated and strained his way out, although it took him an agonising 17 minutes and 35 seconds. All of this and then the Milk Can Escape yet to come. The audience must have been at a fever pitch of excitement and anticipation.

The Western Daily Press described the Milk Can Escape:

‘The new mystery consists of an air-tight and water-tight galvanised can, with cover provided with clasps for six padlocks. After the can is filled with water and Houdini is locked inside, and the whole placed in a cabinet, and in a few minutes the apparently impossible feat of escape is accomplished. The performance was accorded in Bristol, as elsewhere, a great reception.’

You can imagine the throbbing mass of the audience, all captivated by Houdini’s apparent daring and bravery – would he do it ? How did he do it? The tantalising possibility of failure and death. But what of Larry and Violet and the other support acts backstage? What was it like for them? Unlike plays and other dramatic forms there was no sense of a final bow for the acts on a music hall stage. You did your turn and usually left the theatre. As the closing act Houdini would have been the only one to receive the final deafening applause of the audience. I wonder if Larry and Violet hung around to witness the spectacle, lurked in the wings to get a glimpse of Houdini at work? Or sat in their dressing room and felt the impact of the tension and then thunderous applause when the escape was done. Or had they headed back to their theatrical digs? There is always the possibility that Houdini was staying at the same digs. Was Houdini viewed as anything above the ordinary in terms of fellow artistes? After all, the music halls were teeming with conjurors, escape artists and muscle men and Houdini to them might not have been the semi-mythical figure he is viewed as today.

At the end of that week, Houdini was off to the Alhambra in Brussels to showcase the Milk Can Escape there, then heading onto Paris. However, he was soon back in the British Isles and for the week of 5 July 1909 he was at the Hippodrome, Brighton. And he was reunited once again with Larry and Violet who too shared the bill. Almost friends by now, I like to think!

Notes

The Bristol Empire was demolished in the early 1960s to make way for a new ring road. Cary Grant had his first job there as a lime-lighter.

Houdini continues to capture our imaginations – whether via children’s books or TV series. He was most recently televised in ITV’s Houdini & Doyle. For all things Houdini, I recommend John Cox’s website Wild About Harry.

Thanks as always to The British Newspaper Archive.